|

Brad Snyder remembers the beautiful sunrise over Afghanistan on September 7, 2011 with crystal clarity. That’s because it was the last one he ever saw.

Within hours the US Navy bomb disposal expert lost his sight when he stepped on an IED. As he lay in darkness, he was convinced he’d died. So when a doctor told him he was blind, the message Snyder heard was surprisingly upbeat: “You’re alive…” Three weeks of intensive care later, he began the laborious process of learning to do daily tasks all over again – without vision. “The biggest barrier to success was mobility,” he tells me. “I had the capability, I had the right mental attitude. But at that point I didn’t know how to get out of bed or cross the room, let alone leave the hospital. “So the way forward was to make sure every step was better than the one before, adopting the approach known in Japan as ‘kaizen’ (continuous improvement). At first I didn’t even know what a cane does, so I learned to use that to cross the room. That’s better than yesterday. Next I reached the nurses’ station outside my ward: better still. “Within five weeks I was transferred into a rehab ward where I was outside walking. I ran 5km at the eight-week mark. After 12 months I was competing at the Paralympics in London. So it was a quick process. But with that kaizen mentality, within 365 days even a goal medal is possible…” No kidding. Having swum for his Naval Academy, Snyder was ushered back into the swimming pool while he was still an inpatient. In a plot twist that sounds scripted, he took his first Paralympic gold medal – in the 100m freestyle – on the first anniversary of his life-changing accident: September 7, 2012. Never one to shirk a challenge, Snyder then readopted this “kaizen” mentality to start four years of work towards his next “impossible”: the world record. “The London race was a spiritual victory but Rio was another level,” smiles Snyder. “When I said I wanted the world record I didn’t think it was possible. I still doubted it until I dived in, when I felt like magic the whole way. I had the energy, I was moving super fast and when I hit that wall I knew it was mine.” While this timely visit to the Zone crowned Snyder as king of the Paralympic pool, he insists he’s “one of the worst blind guys there” in daily life because it’s still relatively new to him. Eight years on he has learned to click his fingers as he walks, using echoes to judge where walls are, yet he admits each new environment is an adventure. That’s why Snyder is so excited by Paralympic partner Toyota’s global “mobility for all” campaign. He recently made a pilgrimage to the Olympic movement’s spiritual home in Athens for the Toyota Mobility Summit, sharing tales with Paralympic greats including wheelchair racer Tatyana McFadden and British runner Richard Whitehead. These champions of the human spirit have all benefited from technology and Snyder is passionate that everyone should have similar access. “What we’re talking about is human rights, valuing each person equally,” he declares. “It’s about enabling the world’s population to move, regardless of disability, creed or ethnicity. The social implication of that is very powerful…” As for Snyder it’s onwards and predictably upwards. His next challenge is the mother of all events, the paratriathlon. Roll on Tokyo 2020…

0 Comments

|

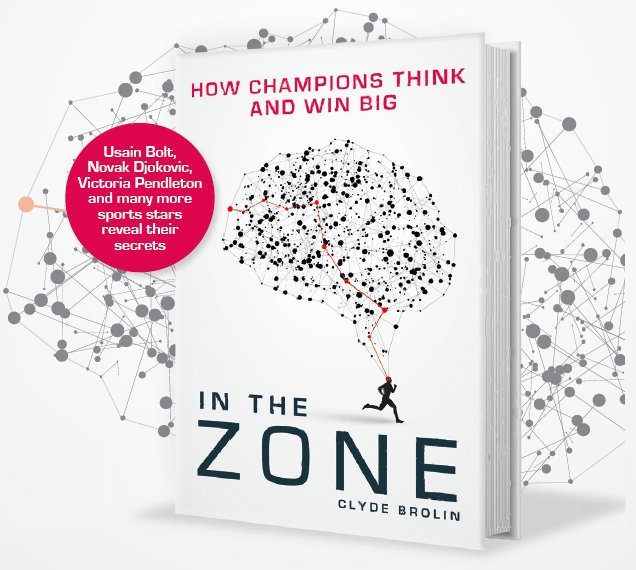

AuthorClyde Brolin spent over a decade working in F1 before moving on to the wider world of sport - all in a bid to discover the untapped power of the human mind. Archives

October 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed