|

South Africa’s victory at the 2019 Rugby World Cup is one of those occasions when sport’s script really does seem written by higher forces. Led by inspirational captain Siya Kolisi, the Springboks arrived in Japan on the back of a rough few years – in rugby terms. But they had a secret strength that bonded them together: playing to unite a nation that had endured a rough few decades. The speeches coach Rassie Erasmus gave in the build-up to the final against England sum up this approach. What is pressure? It’s not having a job, or not knowing where the next meal is coming from. Rugby pales into insignificance by comparison. Those were the people this team was playing for – and it led to a unity rare in sport. At this month’s Laureus World Sports Awards in Berlin, where the Springboks earned the Team of the Year award, it was a huge privilege to quiz Kolisi about how his team generated such collective belief ahead of the biggest day of their lives. ‘We had a coach who believed in us,’ Kolisi told me. ‘Coach Rassie knew what we wanted to achieve, as did all the management, the physios, everyone. All we had to do was work as hard we could to make sure we played the best game on Saturday. We watched tapes every day so we saw every player on the opposition and knew how they played. Doing that over and over again makes you start believing in yourself. Then you don’t have to worry about anything… By Thursday you’re already psyching yourself up mentally – because we’d prepared throughout the whole week. That gave us a lot of confidence, so we went into the game without fear. We just wanted to focus on doing our best.’ The result was one of the most dominant ever World Cup Final performances. Indeed such was the physicality of the first 15 minutes that scrum-half Faf de Klerk recalls feeling such ‘intensity’ from the team – even when things weren’t going right – that he was already convinced they could pull it off. Did it feel written? Not quite. Kolisi offered me the gentle reminder that: ‘We still had to play’. But by midway through the second half they were running riot. If you want a good laugh, check out Francois Louw’s answer to my press conference question about how that really felt on the pitch in the YouTube video below. Then gain some perspective from Schalk Brits on what the eventual result meant to the nation of South Africa…

0 Comments

The news that Formula 1 personnel from Mercedes and other teams were held up at gunpoint on the way out of last weekend's Brazilian Grand Prix at Interlagos sadly comes as no surprise.

It is 25 years since Ayrton Senna memorably remarked that ‘the rich cannot afford to live on an island surrounded by a sea of poverty.’ It was Brazil, his beloved home country, that inspired the sentiment. But Formula 1 is an archetype for the world’s polarisation between haves and have-nots. The increasing isolation of a protected environment like F1 were driven home to me during one attempt to drive home from the 2006 Brazilian GP. The road out of the Interlagos circuit runs past one of São Paulo’s many favelas. Our car stopped at a traffic light when out of the darkness came a group of teenagers carrying guns. This is a common occurrence and locals know to open their doors and give them what they want. But when they targeted us our European driver reacted quite naturally by trying to get away, unaware the traffic ensured there was no escape. Now angry, one guy tried to kick the passenger door in before firing shots in the air. It now felt rather too late for the pleasantries of offering our stuff. All we could do was duck and for second after agonising second we sat there like lemons, utterly helpless and simply hoping not to hear another bang. The gang hesitated, perhaps thinking the car was armoured or, more likely, that it would be more trouble than it was worth to shoot these clueless, cowering foreigners and block the traffic. When the lights changed and a gap opened up ahead, our driver floored it. Lucky? You bet. But I tell that story only to illustrate this is the inevitable conclusion of global policy that continues to make the rich richer and the poor poorer. This has long been the case in Brazil but it is increasingly common in other parts of the world. I can more than understand why these kids, who have precisely nothing in material terms, think their only way out is to grab from someone who has everything. They have been no more misled about what really matters than the grand prix world that believes its own hype about the power it wields. When Formula 1 meets favela in a power battle there is only one winner. In the real world version of ‘paper, stone and scissors,’ pistol trumps pitpass. Since this incident, the sport’s big players use armed guards and bulletproof cars in Brazil – amply illustrating how perceptive Senna’s point remains decades after his death. The way things are going the rich may indeed end up with ‘everything’. But if they can enjoy it only within a prison of their own making encircled by high walls, security fences and bodyguards, is that really worth having? Grand prix drivers have a better chance than most to see the world, visiting 20 countries a year, but they rarely have time to venture out of their hotel or the paddock. Even so not everyone is sucked into the sport’s decadent high life. Senna grew up in considerable wealth yet while he was a tough negotiator when it came to his own contracts he was not solely consumed by personal greed. What he saw on his travels disturbed him, particularly in his home nation, where the gap between rich and poor has long been colossal. It may seem odd for one of Brazil’s richest sons to care about those at the other end of the scale but Senna used part of his wealth to found an organisation for underprivileged children, which has become a major force since his death under the guidance of sister Viviane. Indeed some reckon Senna could have gone on to use his celebrity status to move into a very different world after racing. Long-time friend Jo Ramirez says: ‘I expected him to finish his career with Ferrari. Then I’d have seen him doing something in Brazil to help his people and the children. Ayrton felt he was fortunate, born into a good family with everything on the plate. He made good use of it but he always thought everybody should have a chance. He was so proud of being Brazilian so I would always see him doing something big within Brazil – government, who knows? Ayrton had some very strong views against certain branches of authority so he would undoubtedly have had strong feelings about much of what happens today. He would have succeeded because he was so loved by people…’ It’s not hard to see why - and with such backing, coupled with this healthy disdain for authority, Senna would surely have made a formidable politician. Since this weekend's incidents there have already been calls for even greater protection for Formula 1’s personnel. Where Senna stood out is that he could see the roots of the problem lay elsewhere. Senna’s former physiotherapist Josef Leberer recalls: ‘During my first year with him we were driving through São Paulo when we saw a favela and I asked how he felt when he saw these people. He said it was very hard for him and it hurt a lot, but that you have to be powerful to effect any real change and he was not there yet. He was already doing things for the children even if none of it had become public knowledge. That convinced me he was capable of great things because he wasn’t doing it for the benefit of sponsors or for photoshoots. He wanted to do it. ‘His sport became a vehicle for him to reach a position to help change the world. That wasn’t the case when he started out as an 18-year-old but he had a driving force that kept him going. The more he did it the more he found out why. He was a sensitive man and a thinker who used to carry a lot in his head. He saw the real world and he could see there was so little he could do to change any of it. So his approach was to change himself.’ This is an adapted extract from Overdrive: Formula 1 in the Zone |

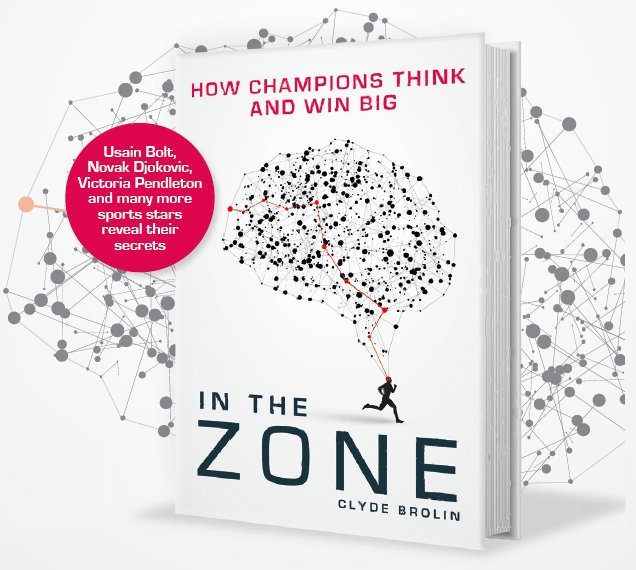

AuthorClyde Brolin spent over a decade working in F1 before moving on to the wider world of sport - all in a bid to discover the untapped power of the human mind. Archives

October 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed