|

Thank you very much to Autosport Grand Prix Editor Edd Straw for having me as a guest on this week's Autosport Podcast to discuss my books In The Zone and Overdrive.

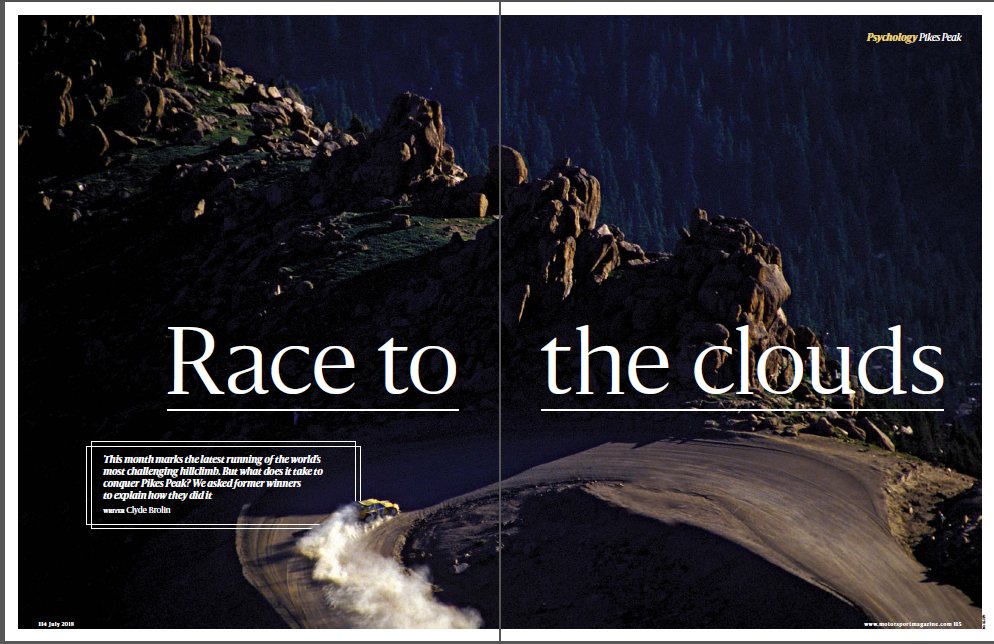

We had a very enjoyable hour of chatting about how the greats of Formula 1 find the Zone - and some of the surreal effects that happen when they get there, from time slowing down to heightened senses to the out-of-body experience. Along the way we talked about Ayrton Senna and two of his biggest fans, who both happened to win the world's two biggest motor races last weekend: Monaco Grand Prix winner Lewis Hamilton (pictured above) and Indianapolis 500 winner Simon Pagenaud, We also discussed Sebastian Vettel, Charles Leclerc, Nico Rosberg, Jarno Trulli, Jackie Stewart and more. The podcast ends with a special treat for race fans: an exclusive clip from my interview with the late Dan Wheldon which opens the prologue to In The Zone. Enjoy... Finally, if you can read Italian click here to find my recent article from Italy's Cyclist magazine featuring interviews with Chris Hoy, Nadia Comaneci, Franz Klammer and more...

0 Comments

Thank you so much to all the media outlets who have taken In The Zone to their hearts and helped spread the word over the past months all over the world. The latest publication to feature the work is the June issue of Ukraine's Megapolis magazine, which carried out an extensive and very well researched interview about the mind of sportspeople and how we can all learn from what they are able to achieve. If you don't happen to be travelling through Kiev this month (whyever not?) and your Russian is up to scratch you can see some of it in the above picture and find the entire magazine online by clicking here. This week I also enjoyed a rare TV appearance on the Motorsport Show hosted by Peter Windsor. We discussed solutions for the widely-criticised 'boring' 2018 Monaco Grand Prix before moving onto a race that is always exciting, the Indianapolis 500, won this year by the aptly-named Will Power (see clip below).

When Takuma Sato took the chequered flag to win the 2017 Indianapolis 500, he became the first driver from an Asian country to win the Borg-Warner trophy. In doing so, he sent the whole of motorsport-mad Japan into raptures.

Sato is also the first 40-year-old for two decades to taste the famous Indianapolis bottle of milk. Yet, like so many of his predecessors it was not the first time he had seen the image in his head. 'I dreamed of something like this since I was 12,' the Japanese racer admitted yesterday. 'You don't just dream about it. Obviously, you prepare for the race. You want to win the race. I had huge ambition and I had to try. I do feel after 2012 I really needed to correct something I left over. 'I knew I could do it. But it was just about waiting for the moment. When the moment comes, I had to give 100% commitment. The last few laps, they were the moment... I just had to believe myself and the car. It came off beautifully. ' The result was indeed redemption after his last-lap crash while battling for the lead with Dario Franchitti five years earlier. But Sato's whole career makes for remarkable reading given how late he began his motor racing life. In an era when most of his contemporaries were filling up their subconscious minds before their age reached double figures, Sato gave them all a decade's head start. He finally caught up yesterday, 20 years later... proof positive that it's never too late to dream big. 'I didn't have opportunity when I was kid,' he smiled. 'I always loved motorsport but I didn't start racing until I was 20. I know it's very late, but I just never gave up. That's maybe why I failed so many times, too. But I made a mistake, learned from it, then tried to get faster and better. 'Age is clearly important for any athlete. Now I'm 40 you have to consider how you're going to perform well and we train really hard. But it's always just heart and the mental strength. You can keep on going...'  Gil de Ferran talks Fernando Alonso through the finer details of racing at Indianapolis (Photo by Chris Owens) Gil de Ferran talks Fernando Alonso through the finer details of racing at Indianapolis (Photo by Chris Owens) Fernando Alonso’s Indianapolis 500 adventure began because he wanted to show he can still race at the front. So far, so good: the Spaniard hasn’t put a foot wrong and he starts Sunday’s race from a fine fifth place on the grid. But he already owes much to the man guiding him through the intricacies of oval racing this month. Brazil’s Gil de Ferran won the Indy 500 in 2003 and, like Alonso, he regularly found the ultimate ‘peak’ of performance that marks out the greats of any sport. Yet he only stumbled into it the first time – during a bout of red mist on the Brazilian street circuit of Florianopolis when he was still racing Formula Fords. ‘I was fortunate that early in my career I accidentally reached a level of performance that seemed illogical to me,’ de Ferran told me as I researched In The Zone. ‘I went off during the race and I bent the car. Under normal circumstances when the pit crew says “go back out” you drive half a lap then say, “God I can’t even drive this thing.” But I was repeating the same lap times – and even going quicker than before the accident. ‘I later analysed the race as always, thinking about what I did right and wrong. But that really confused me. In that situation, which was frankly complete rage, how come I could perform at that level? Whatever triggered it, it wasn’t logical. I’d studied to be an engineer so I always knew two plus two equals four. It can’t equal five. So that didn’t make any sense. There was something irrational about what went on and I realised there was some other place out there.’ The place de Ferran found is the sporting nirvana called ‘the Zone’. But for most sports stars anger is a far from ideal Sat Nav for locating it: rile them up and they fall apart. That’s why sports psychology is usually aimed at inducing states of calm under pressure through techniques like visualisation and meditation. But there are exceptions, not least sailing great Ben Ainslie, who rival teams really shouldn’t consider angering as the 2017 America’s Cup starts on Friday. Gerhard Berger provided another rare exception in Overdrive with his 1997 European GP win just days after his father’s death, during a breakdown in contract negotiations with his team. He duly announced he was quitting Formula 1 before romping to pole, win and fastest lap. There is one crucial benefit to giving up all hope. When you think things can’t get any worse you dump all expectations, get out there and do your stuff. In de Ferran’s case his ‘rage’ also led him back to the pure natural ability he had in bucketloads – and he later sought to rekindle the sensation. ‘Knowing this exists was an important step, but getting there is a completely different challenge,’ he adds. ‘It depended on your emotional state of mind and your ability to Zone everything out. At the time IndyCar races were very strategic, not only about pure pace. So I had to be careful about flying off into another level. At the start of my IndyCar career that was an issue. I pushed too hard and crashed too much. But I kept working and working and working to be able to reach it more often than not. ‘I was good at doing it for qualifying - and particularly on street circuits I’ve had situations I can’t explain. You think “this is it” but there was always more and more and more. I took pride in my feedback about how the car was handling. Usually I was incisive and precise: “I want more front wing.” That’s it. But at times like that I just said: “Put the tyres on and let me go.” I’d come back with only the vaguest recollection. It usually coincided with my best runs.’ Fernando Alonso is no stranger to this racing bliss either, once telling me that this sensation feels like you're driving in a Scalextric. Moreover he rates it better than winning a race, or even winning a championship. Yet victories are often the inevitable result of a trip to the Zone anyway; if the Spaniard can find this special mental state this weekend he has a genuine chance of tasting the famous Indy 500 winner’s bottle of milk. Too much to ask at his very first oval race? Not if you ask his coach… ‘It’s pretty cool when you get there but different sportsmen reach the same level and it’s not just limited to sports,’ smiles de Ferran. ‘I truly believe the human being has a level above what people normally reach, and that you can operate at a whole different level at whatever you want. It even applies on an intellectual level. In my view the mind is elastic. There are absolutely no limits.’ |

AuthorClyde Brolin spent over a decade working in F1 before moving on to the wider world of sport - all in a bid to discover the untapped power of the human mind. Archives

October 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed