|

The Olympics start tomorrow and elite athletes all over the world are dreaming big. For five long years they have dedicated their entire existence to Tokyo, regularly picturing the view as their national anthem sings out to a packed arena.

This is the justification for decades of focus on a single target: every early morning, every mile run through wind, hail and snow, every vomit-inducing gym session. All the pain will make sense when they reach the top of the world. Right? Pity few enjoy this golden pay-off. The rest will fail – very publicly – in full view of their family, friends, nation and planet. That is guaranteed to hurt more than anything they’ve ever felt before. “To fail to make a goal is one thing. To do it in front of two billion people is another. It’s heart-wrenching. When you work so hard and sacrifice so much… I literally felt my soul was being shattered.” These are the words of Missy Franklin: the darling of the Aquatics Centre at the 2012 London Olympics, this ever-smiling 17-year-old American swam to four gold medals and charmed fans with her happy-go-lucky personality. Cut to Rio in 2016 and it was a different story: she failed to reach the final of either of her individual events. Ouch. When I meet Franklin years later the humiliation remains etched in her mind. “Throughout my life everything made sense to me: you work really hard, you make the sacrifices, you do everything you can, then you get faster and achieve your goals,” says Franklin. “That’s why Rio made no sense. I was in my best shape ever, I had my best trainer… and I had the most disappointing meet of my life. “How does that work? It showed me the importance of mentality. Physically I might have been incredibly healthy, but mentally and emotionally I was in terrible health. That makes a huge difference. At 17 I was new; I didn’t have expectations. But now people knew what I did, and I started listening to their expectations. That was so hard, because before the Games started I felt I’d already failed. Even if I took home three gold medals it still wouldn’t be good enough: ‘Oh well, you got four in London…’ “I always swim my best when I’m enjoying myself, but that took all the fun away. I felt so heavy going in; so much pressure. They were the most miserable eight days of my life. It broke my heart to feel like that, because I was at my second Olympics and I wanted to enjoy every bit of the experience. But I’d rather have been anywhere else.” Of course Franklin was not alone. The full scale of the mental health epidemic facing sport has only become apparent in recent years, as athletes come out with stories they may once have kept hidden. It’s not even limited to ‘losers’; the greats have their own demons to face, both before and after any fleeting euphoric high. Franklin didn’t leave Rio empty-handed either, but she returned home with ‘only’ one gold medal – earned for helping her relay team through the heats; she wasn’t entrusted with a place for the final. This would be most people’s pride and joy but it serves only as a reminder of the week Missy’s world fell apart. She used to smile routinely before every race – partly to generate the positive attitude essential to performance, partly to remind herself ‘fun’ was key to everything she did. Now the smiles dried up. The gloom was briefly lifted when she arrived home to find a sea of paper hearts on her front yard. They were covered in messages from local kids saying why Missy was their role model and why they still loved her. She began ‘hysterically sobbing’ out of gratitude to the people who stayed by her side. But it would not be the last time tears flowed as the magnitude of her failure hit home. “The low went on for a while as I dealt with the confusion and pain,” admits Franklin. “I was so humbled by the whole experience, and it takes a long, long time. After that I went through bilateral shoulder surgery so I had to take time away from the water. I’d always been good at swimming, and it always worked out well, so it was easy to say: ‘My identity isn’t based in this.’ Now, for the first time, swimming was taken away – and I realised how much of my self-worth I put into the sport. “When it doesn’t work out, how does that change your view of yourself? I had to take time to sit down with different people and work through: ‘Who am I? What do I value about myself?’ That was unrelated to what I did in the pool, but it takes a long time to grasp that. Now my relationship with swimming will never be the same. So it’s about accepting that; and that non-judgmental attitude towards myself is the most important thing I’ve been working on.” It’s easy to see how an Olympian’s self-image can become so intertwined with what they achieve. Elite athletes live in a bubble where everything is measured, from every training session to every final. That’s fine when things are going swimmingly. When they’re not, self-esteem can sink as fast as their results. Sometimes it takes time away – enforced or otherwise – to regain any perspective. In Franklin’s case her background studying psychology at the University of California gave her some backup. But there is no more brutally effective teacher than life itself. We all find this out at some point, but few of us honestly know how to treat triumph and disaster just the same. That’s why we look to learn from anyone who has already endured hardship and come out stronger on the other side. This is where Missy Franklin has found her silver lining. “My faith is important and one thing that stuck with me for the entire journey was that with God your pain has a purpose,” smiles Franklin. “There are times when you think: ‘This will never be worth it. Why am I having to deal with this? Will I ever get out?’ But everything I went through was moulding me into the woman I was supposed to become. It’s crazy to see how this has changed me. I’m a totally different person to what I was eight, four or two years ago; I’ve learned so much and I feel so strong. “I now realise one of the main reasons we go through what we do is so we can help other people. Now I can talk to friends, athletes or strangers experiencing something similar, and share how I got through it. To see their gratitude and appreciation makes everything worth it.” Still just 26 years old, Franklin made her official retirement from swimming late in 2018. She has since married fellow swimmer Hayes Johnson (and is now known as Missy Franklin Johnson) with their first child due next month. She is as bubbly as ever – but armed with uncommon wisdom for one so young. As such she can expect a full inbox over the coming weeks as her fellow ‘failures’ make their own tearful return from Japan. But why stop there? Let’s face it: we all fail. Often. And it hurts every time. Indeed this modern life of screens has taken things to a new level. It means we can all ingest a daily overdose of apparent ‘good times’ not just courtesy of the rich and famous, but our own friends and family. That’s all we ever show in public too, but Franklin knows it’s when things are falling apart that we really need help. “The main thing I can do is be open about my failures,” she adds. “As elite athletes we feel we have to be composed, confident and tough all the time; especially with social media, people only post the best aspects of their lives. People go on and think: ‘My life isn’t anything like that.’ But nobody’s life is like that. You’re only seeing the good, and nobody’s life is only the good. “We have to recognise it’s not real. If we want to follow an athlete or celebrity, fine, but it’s crucial to realise their lives are not exciting and wonderful all the time. This feeling that we have to constantly compare ourselves is dangerous. Comparison and judgement are two of the most harmful practices a human can do, yet it’s what social media is all about. And what we see can often be so skewed and wrong. It’s OK to be exactly who we are and not this ideal self we post to everyone else. “When we are vulnerable and share the hard times; the bad, the shame, guilt, anxiety and depression, that’s when we impact people. Lots of athletes say to me: ‘I had no idea you experienced anxiety attacks before you raced. I have anxiety attacks, but I can’t believe YOU had them!’ That’s what they can relate to, and where they really need help. We don’t need to help someone get through a good time, right?”

0 Comments

|

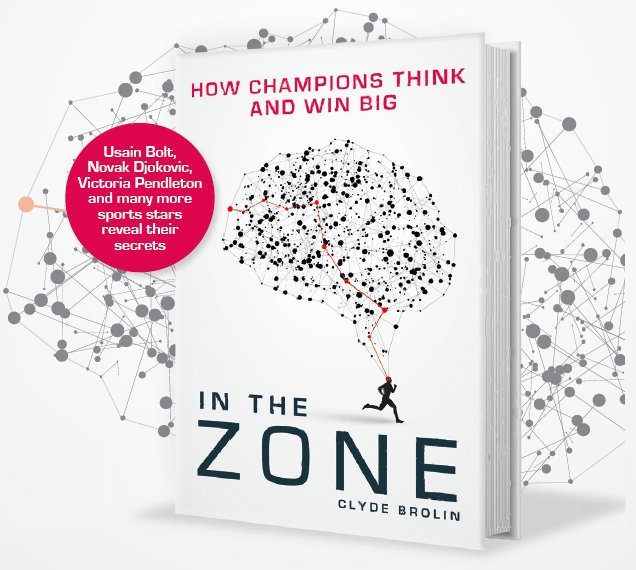

AuthorClyde Brolin spent over a decade working in F1 before moving on to the wider world of sport - all in a bid to discover the untapped power of the human mind. Archives

October 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed