|

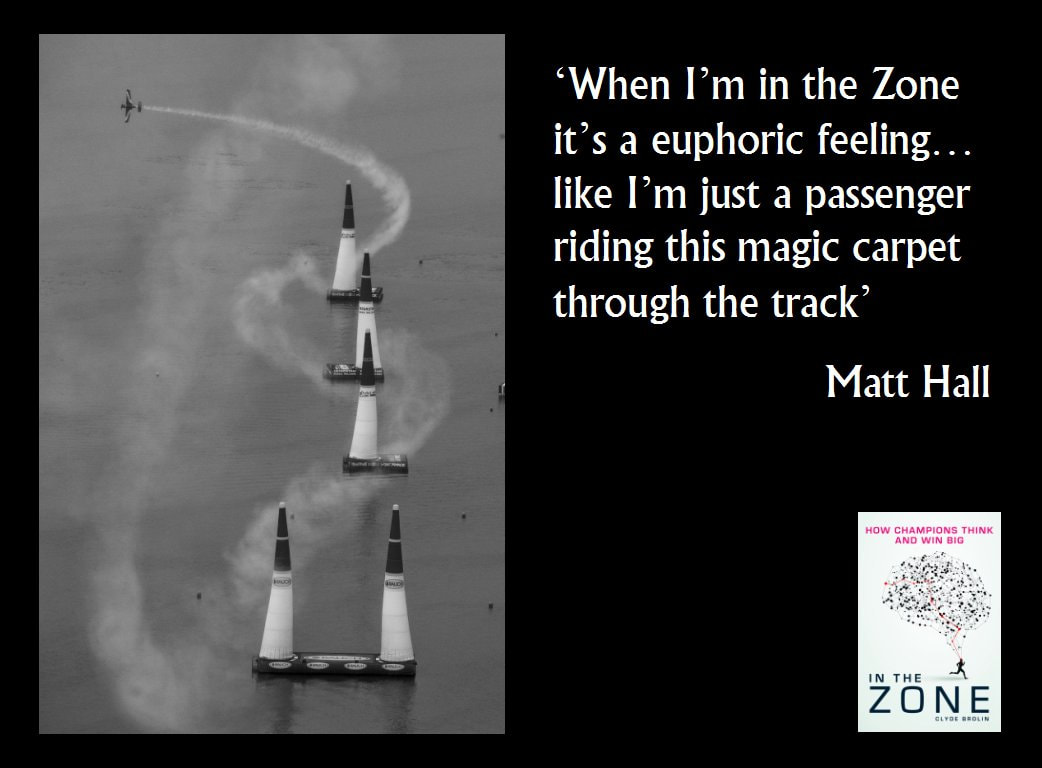

The level of expertise needed to be ‘in the Zone’ is not limited to sport. When Captain Chesley ‘Sully’ Sullenberger’s Airbus struck a flock of Canada geese after take-off in January 2009, he made the apparently snap decision to land on New York’s Hudson River. He later declared he’d spent 42 years making small deposits in a bank of experience; that day his balance was sufficient to make a ‘very large withdrawal’. This led Sully straight to the Zone when it mattered, saving 155 lives. No one is born able to fly an aeroplane, just as no one is born driving a car. To get good at either requires long hours as the brain gradually learns how to interpret the sensations sent in from all over the body as the vehicle rolls and yaws, converting this mass of data into instructions to send back to the limbs perched on the controls. This eventually crafts an ability to complete even the hardest tasks without thinking. Still, the proficiency of a lifetime of practice will be no use if you can’t access it on the one day, the one second when it really matters. If you ever suddenly find yourself having to think about what you’re doing, it’s a one-way street to remembering in vivid detail how staggeringly complex your skills were in the first place. Some professionals have an even bigger bank to draw on – such as British Airways 747 captain Paul Bonhomme, who doubles as a triple world champion in the Red Bull Air Race. Since 2003 this event has claimed the title of the world’s fastest motor sport as its single-seater planes twist, spin and loop, speeding at up to 250mph between a series of pylons just 25 metres above land and sea. Far from the crazy daredevils they appear, pilots are invited to compete only after proving they are among the world’s finest aerobatics aces. Bonhomme’s 19 career wins rank him as the all-time best of the best. ‘Whatever you’re flying, you have to be in the right mood,’ says Bonhomme, who retired from racing after his third title in 2015. ‘It varies if it’s an air race, an aerobatic display or just a flight from A to B. You’re supposed to fly a jumbo jet so far within safety levels it should be relaxing. But depending on how extremely you’re operating an aeroplane, you have to be in a better mood or, yes, “in the Zone”. ‘In air racing the challenge is getting out of a tricky situation. For that you need years of tumbling, flicking, stalling and spinning. That once saved my bacon in an air race and I know others who had similar situations. You need a heap of experience before you go air racing, just as you would want the best stick and rudder pilot flying an airliner. Ironically in both cases if you’ve got it hopefully you won’t need it. ‘Air racing is extraordinary because everything else in aviation is super-safe whereas this is suddenly using motor racing ethics. So there are two fears: the fear of not doing very well and the fear of frightening yourself – or worse. You need to get the mix in clear proportion. It doesn’t really matter if you come fifth instead of first but it really does matter if you’re not around at the next race…’ Australian ace Matt Hall nearly got that balance wrong during a 2010 race in Canada when he skimmed the water with his wingtips. He has since become one of the sport’s all-time greats by learning to manage his self-belief to be ready to peak – including an elaborate mental build-up over the course of a race weekend.

Hall approaches his mental groundwork with the rigour you might expect of a former Wing Commander in the Royal Australian Air Force. His countdown increases in rigidity as take-off time approaches, starting with a stretch first thing and a walk to clear his mind. Media interviews fit into the morning before the daily pilots’ briefing. Within the final hour he lies down in his hangar for precisely 21 minutes, with music building to a crescendo to wake him up with half an hour left. Then comes another set of mind flying, a last look at notes and video before he gets ‘suited and booted’ to be in his plane with twenty minutes left – all with an ongoing musical soundtrack until he swaps his headphones for his helmet six minutes before take-off. ‘I have set times for visualising the track, otherwise you end up over-preparing and you become stale,’ Hall tells me in the book In The Zone. ‘In the hours leading up to a race, on the hour I spend five minutes thinking about it. Then with one hour to go I’m in a formal routine where everything is planned by the minute so I’m not distracted and I have zero stress. The stress only comes when you start looking too far ahead. ‘Music works for me and I always listen to the same set of songs in a row. Every song represents something to me. There’s a song to pump me up when I’m getting dressed, then more relaxing songs as I visualise the track. When I’m strapped into the plane it’s rock – not hard rock but happy rock: “I’m happy to be doing this, my life’s not depending on it, I’m just here having fun and racing planes.” ‘That’s the last thing I do so when I start the engine so I know I’ve done everything I can, I’m confident and really happy to be here. Then it should go well. If you’re too pumped up you’ll just smash it. If you go out hoping you don’t make a mistake it won’t work because you won’t fly aggressively enough or you’ll be really tentative. You have to go in saying “How good is this? I can win this, let’s have a crack at it...”’ Despite everything Hall has long been the pretender, finishing second in the Red Bull Air Race world championship three times. When it was announced the series would not be continuing after 2019 it seemed his time was up. Yet in one of sport's great stories of redemption he somehow pulled it off, finally fulfilling his long-held dream in Japan last month (pictured above). The Australian may now be ‘reigning’ Red Bull Air Race World Champion forever, but something tells me there is one sensation he’ll miss most of all…. ‘On the best runs you don’t think about two gates time,’ he smiles. ‘You think about this gate coming up right now and the feel of the aircraft. That’s all. That’s when I know I’m on a really good run – because there’s not a single thought of doubt in my mind and not a single thought of the future. They talk about being “in the Zone” and when I have a good run, I definitely know. It’s a euphoric feeling. I can’t hear the engine any more, I’m just a passenger in the aircraft, just riding this magic carpet through the track.’ This is an adapted extract from In The Zone: How Champions Think and Win Big

0 Comments

Today marks two years since we lost one of the world’s great free spirits and adventurers, Hannes Arch.

As a youngster growing up in Austria’s mountains, Arch spent his time climbing. He took up hang-gliding aged 15 before a switch to paragliding and BASE jumping. The Austrian would become a true pioneer as the first man to leap from the North Face of the Eiger and the first to land a paraglider on a hot air balloon. Arch later allowed himself the relative comfort of an aeroplane, seeing off the world’s best aerobatic pilots to win the 2008 Red Bull Air Race world championship. ‘If you do all those really dangerous sports you know exactly where you are,’ Arch told me in a 2014 interview that features in the book In The Zone. ‘Nobody wants to die, especially me, because I really love life. Sometimes you turn around and don’t jump because you know it would be dangerous. ‘These sports also teach you to handle risk so they are the perfect preparation for air racing: focus is the most important factor for surviving dangerous sports, but also to be fast in air racing. The interesting thing is that if you are in this mindset – focused 100 percent on flying without having to deal with thoughts of crashing or risk – you get really fast. And when you get really fast you realise you are always really safe. When you start to risk and play unsafe it slows you down.’ Air racing is such an extreme sport it forces pilots into clearing their minds – fast – and it’s the same with all who push to the edge. Arch sure was fast, too. Overall he won 11 races, finishing in the Red Bull Air Race top three for five straight years. Elsewhere this ‘lover of life’ invented the Red Bull X-Alps: a punishing dash from Salzburg to Monaco by foot or paraglider. The latest edition took place in July, 2017 and the event will continue as a living legacy to its crazily creative craftsman. Arch also used his skills as a helicopter pilot to help out with charity efforts in Nepal by ferrying supplies to remote mountain communities. He was flying a helicopter from a hut in his beloved Austrian mountains when he crashed and died on September 8, 2016 – just shy of his 49th birthday. Thanks for all the memories, Hannes. And keep flying high. Mindfulness. Pure focus. Total concentration. That magical sensation of quieting the mind and living in the now… These concepts have only recently breached mainstream Western consciousness, yet over the last decade they have gained ever greater prominence. But it’s not just about sitting cross-legged on a mountaintop, or even staring at a candle in the living room. The path to ultimate inner peace can appear anywhere – and a shortcut is often found in conditions that are diametrically opposed to any idea of ‘calm’. Sport is a classic example, especially those involving extremes of speed – such as the world’s fastest form of motorsport, the Red Bull Air Race, where single-seater planes twist, spin and loop just metres above land and sea. In the new book In The Zone, Germany’s reigning air race world champion Matthias Dolderer insists: ‘You’re so focused and concentrated there is nothing else that can distract you. You don’t have time and you are fully 100 percent concentrated on what you’re doing. When you fly, whatever happened before this is gone. Actually, to fly in the racetrack is the best way to get rid of all distractions.’ Mindful? Focused? Concentrated? Check. This clutter-free mind is crucial for sport, hence why techniques to induce this state of mind are now commonplace. Legendary NBA coach Phil Jackson used this approach to mould his successful Chicago Bulls and LA Lakers teams, while Nico Rosberg admits he turned to meditation to find the mental strength to beat Lewis Hamilton to the 2016 F1 world championship. But really there’s nothing new about this hunt; ‘Zen’ Buddhism is a derivation of the Indian Sanskrit ‘dhanya’ meaning meditative concentration. Today Japanese air racer Yoshihide Muroya makes for a good example as a practitioner of zazen, which translates as ‘sitting meditation’. ‘Meditation helps me because it’s mental training,’ Muroya tells me for In The Zone. ‘At an air race I do it every morning. I use it to focus on myself, just to calm down and take away the extraneous thoughts that have been going through my head. In racing there’s no time to think so you need to be focused and automatic.’ Something must have paid off: Muroya heads to his home race in Japan’s Chiba this weekend looking for a repeat of his debut win at the same venue last year. He also won this year’s latest race in San Diego to raise hopes of a Japanese motorsport double in a week following Takuma Sato's Indy 500 win. Best of all, Muroya insists we can all reap the rewards of ‘looking inside’ even if our own office moves rather slower. ‘Meditation is good for flying and it’s a big help for life too,’ he smiles. ‘Everyone can benefit from it. We all have so much going round our brains all the time and we normally look outside so it’s quite difficult to look deep inside. But it’s really good to calm down and looking inside helps make life easier for anyone.’ Read In The Zone to hear more from British Red Bull Air Race world champions Paul Bonhomme and Nigel Lamb plus Canadian racer Pete McLeod, among 100 exclusive interviews with stars of world sport |

AuthorClyde Brolin spent over a decade working in F1 before moving on to the wider world of sport - all in a bid to discover the untapped power of the human mind. Archives

October 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed